Change 11: Learning in Times of Abundance

November 14, 2011So now HP is dropping webOS, mobile, and

August 19, 2011So now HP is dropping webOS, mobile, and PCs altogether? http://bit.ly/oa7D92 Follow the bouncing ball, folks.

The Factory Model of Higher Education

August 18, 2011

There are a lot of reasons for thinking that higher education has been on a wrong track for the last fifty years or so. I have mentioned some of them here and here for example. As I discuss in my book, current thinking about how to manage a university (particularly a large one) is driven by an industrial model. It’s not an idea that I invented. Fifty years ago, Frederick Rudolph, the great historian of universities, talked in pretty explicit terms about the “assembly line”:

On one assembly line the academicians, the scholars were at work; from time to time they left their assembly line long enough to oil and grease the student assembly line. . . . Above them . . . were the managers—the white- collared chief executive offi cers and their assistants. . . . The absentee stockholders sometimes called alumni, the board of directors . . . the untapped capital resources known as benefactors . . . the regulatory agencies and commissions in charge of standards.

You can understand how all of this got started at the turn of the last century. The great benefactors of higher education were industrial leaders like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. They wanted the fairly chaotic system of schools, colleges and universities to establish ground rules. What constituted credit? How were students defined? Where was their money going to go? The only real models they had to rely on were the brand-new manufacturing models that valued high quality at low cost. In these models, variance is the enemy. These were the models that were imposed on American higher education. We can still see their echoes in testing and accreditation bureaucracies.

But Carnegie-era industrial policy had no way of foreseeing the explosive growth that the last half of the twentieth century brought to American institutions. I am not alone in thinking that 19th century industrial policies are at a dead end in higher education.

The Prezi presentation at the start of this post, is an overview of how badly the factory model has led us astray over the last generation. Maria Andersen — a community college professor — has been cannily accurate in her portrait of modern higher education practices, and I have become a fan of her analysis of the state of our systems.

There is no sound for this video clip unfortunately. The clip below has sound but the video is pretty bad. I don’t know what to tell you about how to watch these presentations. If you have two computers you might consider using one for audio and the other for video.

What is a MOOC?

August 17, 2011

Yesterday’s post prompted questions about what exactly a MOOC is. It even prompted a note or two about why anyone would choose a stupid name like MOOC. I can help with the first question. Here is a video explaining the concept. I can’t help with the second question, but if you have a better term please let me know.

SmartMoney’s “payback” survey of 50 t

August 12, 2011SmartMoney’s “payback” survey of 50 top-priced schools shows which alumni are reaping rewards in the job mark… (cont) http://deck.ly/~U7fPG

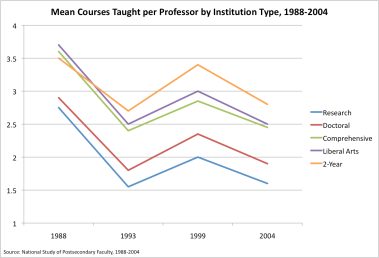

Another View of Faculty Productivity

August 4, 2011 Crazy claims about faculty productivity are bouncing around like ping pong balls. Public research universities in Texas are getting more than their fair share of attention from agenda-driven politicians because their professors are not spending enough time in class. They’ve even invented a classification system based on this one-dimensional view of academic life:

Crazy claims about faculty productivity are bouncing around like ping pong balls. Public research universities in Texas are getting more than their fair share of attention from agenda-driven politicians because their professors are not spending enough time in class. They’ve even invented a classification system based on this one-dimensional view of academic life:

- dodgers

- coasters

- Sherpa

- pioneers

- stars

I don’t think I’d want to be a coaster, but to be honest, I wouldn’t want to be a Sherpa, either.

CCAP’s Richard Vedder has looked at the same data through a conservative economic lens and concluded that significant costs savings can be found by adjusting teaching loads — upwards, of course. Like CCAP I think there needs to be more emphasis on undergraduates, but just lopping off a part of an institutional mission is not the way to do it. Unless, of course, you are of the opinion that everything outside the classroom is overrated in American universities.

Maybe I travel in different circles, but the faculty workday appears to me to be an already overstuffed suitcase. Anyone who wants to cram in another sock needs to take a look at what’s already there. Mission creep, bureaucratic bloat, crushing compliance requirements, and the willful bliss with which research universities give away research time have filled every nook and cranny.

I talked a few weeks ago about how research is given away, and it’s a topic that always draws phone calls and email. But let’s take a look at the same data that CCAP uses. The John William Pope Center recently published a national analysis of teaching loads. It should come as no surprise that they have gone down over the last twenty years, but more interesting is the trend.

The decreases virtually track the increased workload by program officers at Federal funding agencies. But since staff spending at agencies like NSF has been stagnant for twenty years, program officer workloads really just measure proposal submissions.

Why the decrease at Carnegie Research and Doctoral institutions? According to an NSF study the tendency in most NSF program offices is to deliberately underfund project proposals. Over half of the researchers surveyed reported that their budgets had been cut by 5% or more and that their grant duration had been slashed by 10% or more. There is little room for padding an NSF budget, so these are real cuts in funds that are needed to successfully complete a research plan. One more sock stuffed into the productivity suitcase.

What does a winning proposal cost? The same study reported:

…PIs’ estimate of the time it took for them and other people—for example,

graduate assistants, budget administrators, and secretaries (not including time spent by

institutional personnel)—to prepare their FY 2001 NSF grant submission was, on average, 157

hours, or about 19.5 days. It should be noted this is the time for just one proposal that was

successful.

Since the NSF success rate is currently around 25%, that’s about 80 days just to prepare a winning proposal. Add to that the time needed to conduct the research that goes into every proposal submission, and you get a rough idea of what needs to be funded just to make research pay for itself. This is lost productivity, and it shows up in reduced faculty teaching loads.

The trends at Comprehensive, Liberal Arts, and Community Colleges measure something slightly different: each of these institutions sees climbing the Carnegie hierarchy as important to their missions. For example, NSF awarded $350M to community colleges last year. The lions’ share of these funds went to worthy projects to train technicians, broaden participation in the sciences and support research experiences for returning veterans. Individual awards for some of these programs start at $200,000 and solicitations for larger, center-scale proposals are encouraged. Like their research cousins, Community Colleges reduce classroom productivity to compete for federal research awards. An institution with an undergraduate research mission can easily get drawn into a system they cannot afford. And the data supports the claim. For the period covered by the Pope Center report, proposal submissions from these institutions have increased almost in lockstep with lost classroom productivity.

Measuring technical productivity is not a job for the faint of heart. You have to take into account all uses of time, and outcomes that are often unpredictable events influenced by factors beyond an organization’s control. Modeling productivity is complex and frequently contentious, but I have yet to find anyone who seriously proposes measuring engineering productivity by the amount of time spent at a single activity. Outside higher ed.

There is an easier explanation for the disturbing downward trend in teaching loads. It is mission creep. There is really only one way out, and it has nothing to do with cramming more into a Texas-sized suitcase. How about if everything from sponsored research to intercollegiate athletics had to pay its own way? The academic suitcase is full of stuff already. Let’s figure out where to put everything else one sock at a time.

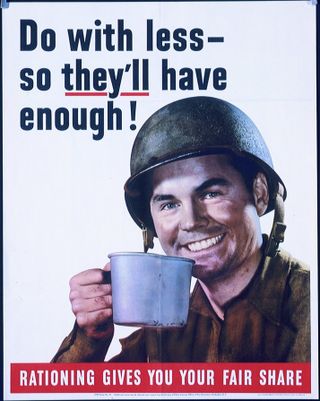

Another View on Doing More With Less

July 12, 2011The July 7th edition of The Economist features this article on “How to Make College Cheaper.”

http://www.economist.com/node/18926009?story_id=18926009.

I wrote on this subject last summer (here and here, for example), but there has been much discussion in the news this year about the $10,000 undergraduate degree, so I thought it would be good to let you know that the ideas are still in play.

It is a concern that so much of the current discussion is driven by ideology. I will have something to say about that in a later post.

Culture, Rose-Colored Glasses, and the Michigan Bottle Scam

June 28, 2011NEWMAN: Wait a minute. You mean you get five cents here, and ten cents there. You could round up bottles here and run ’em out to Michigan for the difference.

KRAMER: No, it doesn’t work.

NEWMAN: What d’you mean it doesn’t work? You get enough bottles together…

KRAMER: Yeah, you overload your inventory and you blow your margins on gasoline. Trust me, it doesn’t work.

JERRY: (re-entering) Hey, you’re not talking that Michigan deposit bottle scam again, are you?

KRAMER: No, no, I’m off that.

NEWMAN: You tried it?

KRAMER: Oh yeah. Every which way. Couldn’t crunch the numbers. It drove me crazy.

Even Kramer got it. Fundamentals matter, but there is a persistent legend in many engineering organizations that culture trumps the bottom line. It’s a legend that propagates because, as change management consultant Curt Coffman has provocatively noted, “culture eats strategy for lunch” when it comes to execution. What Coffman and others who talk about “soft stuff” don’t tell you is that in the end culture doesn’t matter.

The reality is is this: culture only trumps the bottom line in organizations that are heading in the wrong direction. It’s easy to see why: bad execution can be excused when it is in the service of a higher calling. Sometimes — the legend goes — cultural purity even demands failure. Briefings that begin with a retrospective tour of a company’s glory days or the exploits of its leaders are not going to end well. It’s a malady that afflicts start-ups, Fortune 100 companies, universities, and political office holders.

It was a rare meeting at Bellcore or Bell Labs that did not begin with a bow to a century of innovation and accolades. Theirs was a tradition so rich that it was bound to color all projects in perpetuity. I knew a business development managers who intoned “WE ARE BELLCORE!” at the start of engagements. It always sounded to me like a high school football chant designed to cow the opposition.

The remnants of the Army Signal Corp research lab at Fort Monmouth New Jersey had long dispersed by the time I interned there in the early 1970’s, but stories of the famous scientists who once stalked the cavernous halls of the enormous hexagonal building near Tinton Falls were retold to each new class of PhDs as if the great men would be dropping in any moment to don lab coats and resume their experiments.

Start-ups are not immune, either. A few weeks ago, I was nearly ejected from a meeting with a CEO who was raising early stage money for suggesting that the distinguished professors who had founded the company might have had less than complete insight into market realities.

The “We are great because…” meme is propagated by leadership at all levels. Even in this age of the decline of the celebrity CEO, countless university and corporate websites are travelogues for executive jaunts to far-flung campuses. Supporters of one prominent Silicon Valley CEO would muse to anyone who cared to listen: “I wonder what it feels like to always be the smartest person in the room?” The phrase found its way into an industry analysts’ briefing at the very moment that the company’s stock was falling off the edge of a cliff. I watched the faces of the analysts, and it was clear that they were pondering entirely different questions.

I’ve had my share of run-ins with employees who were not at all shy about using vaguely remembered words of long-departed leaders to pit culture against execution. In one instance, a series of patents led to an ingeniously conceived system for streaming audio and video from conference rooms and lecture halls. Unfortunately every cost projection showed that the effort required to install and maintain the equipment swamped any conceivable revenue stream. When I confronted the inventors with the inevitable conclusion, I was excoriated in the most graphic possible terms because I had not taken sufficient account of the intellectual beauty of the system. The crowning blow: “Dr. [insert the name of any of my predecessors] would have understood my work!”

On another occasion, I was called upon to invest heavily in a newly conceived and revolutionary mathematical method that would transform not only our business but scores of related industries. The inventors’ local managers had been completely sold on the idea and were willing to put a substantial portion of their margins at risk to develop it.

Key to the idea was the notion that every textbook in the field had been written by authors who willfully ignored the power of the new theories. The invention involved an area in which I had done research in the past, but I couldn’t make much sense of the claims. I dutifully sent drafts of patent disclosures to experts, but the feedback was discouraging. The claims in the patent disclosures were either false or so muddled that further analysis was useless.

I pulled the plug. Reaction was swift and heated. Here’s what it boiled down to: the founders would have had faith in the employees, and I did not. They were right about me, but not about the founders.

It is in the nature of engineering organizations to reconstruct the past to suit the present. Hewlett-Packard was famous for such rose-colored glasses. When then-CEO Carly Fiorina combined ninety or so business units — each of them concentrating on a slice of a business that overlapped with a half-dozen others, driving down operating efficiencies and, with them, margins — into a total of six, howls could be hear from every HP lab on the planet. “Bill and Dave would not have done that to us.” A casualty of Mark Hurd’s rapid moves to salvage the strategic advantages of the two year old Compaq merger by slicing investments that did not have a clear path to revenue was the revered software laboratory at HP Labs. “Destroying the culture!” cried the masses.

Now I happen to think that both moves were unwise, but not because of any cultural imperative that had been handed down from Bill and Dave. The numbers were seldom that hard to “crunch”. It always boiled down to fundamentals. Risks were taken, but only when the fundamentals made sense.

It is a unique fiction in Silicon Valley that Bil Hewlett and Dave Packard were friendly to anything but an engineering culture that demanded results and held managers personally accountable for their decisions. I once got in trouble with the company’s director of marketing and communications for suggesting otherwise in a public forum.

“Culture” often reared its head during my tenure at HP — usually as an excuse for ignoring business fundamentals. It was a problem that plagued Joel Birnbaum, my precedessor, Dick Lampman, head of HP labs and others over the years. On those occasions, I was happy to have the words of Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard to fall back on.

I’ll talk about that in my next post.

Two New WWC Blogs

August 28, 2011WWC has always been about Innovation, but the amount of traffic devoted to innovation in higher education has grown over the last two years. In fact, the most popular articles are the ones that talk about how to transform colleges and universities. I’ve tried to categorize the posts accordingly, but it now seems like a good idea to create separate WWC sites, one devoted exclusively to innovation in education and the other devoted exclusively to private sector innovation.

Of course, I am not taking the term “exclusively” too seriously, so you will still find comments, articles, and feeds that relate to both. But for the most part, the worlds of execution and innovation will be bouncing off each other at a new site called Innovate.WWC. It can be found at

http://innovate-wwc.com.

Meanwhile all of the inconsistencies that make universities such interesting places will be colliding at Innovate.EDU which is located at

http://innovate-edu.com.

Regardless which site you visit you’ll find all the old posts, and I will keep them on this site as well.

Posted in Comment and Review | Leave a Comment »